Fed freaks markets with hawkish turn

Plus China tackles moral hazard, Iran elects Raisi and Toshiba shareholders revolt

Thank you for reading another edition of Contention! This week we have about seven minutes of morally hazardous dissident business news. We cover:

Fed freaks markets with hawkish turn

China keeps reducing risk

Rapid Round: Iran elects Raisi and hopes for deal restored, Toshiba faces reckoning for corporatist moves

If you find value in analysis like this, please share Contention with others who might appreciate it too.

Fed freaks markets with hawkish turn

Stocks plunged last week with the Dow losing 3.5%, the S&P 500 1.9% and the Nasdaq 0.3%. It was the S&P’s worst week since February and the Dow’s worst since October.

Everyone knew what the story of the week would be: the Federal Reserve’s most important meeting in months. But the bank still managed to surprise markets with a move to the hawkish side, its latest choice in the no-win mess of its own making.

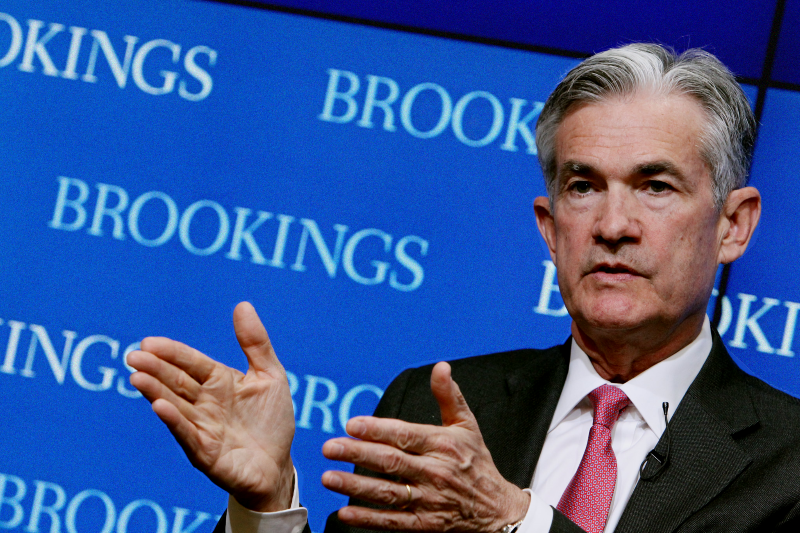

The meeting was the Fed’s chance to talk about how it will fulfill its dual mandate -- price stability and full employment -- in the wake of multi-decade inflation records and a labor market experiencing both elevated unemployment and shortages. On Wednesday, Chairman Jerome Powell announced that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) had decided to:

keep the Fed funds rate -- its most important rate, what banks charge each other -- near zero

maintain $120 billion a month in Treasury bond and mortgage-backed security purchases

raise interest rates on both excess bank reserves parked at the Fed (IOER) and on overnight reverse repos, by 0.05% each.

Nobody expected a move in the funds rate, but the meeting’s biggest surprise came from the “dot plot” -- the FOMC’s anonymized estimates of future rate expectations, indicated by dots on a timeline. In March, the dot plot indicated that nobody on the committee thought the bank would raise interest rates any time before 2024. Now the average expectation is for two increases in 2023.

This is a significant expectation shift towards tighter monetary policy. Seven of the 18 committee members now anticipate a hike as soon as next year, 2022.

St. Louis Fed President James Bullard was not among those seven -- he isn’t on the FOMC this year, but will be next year. Bullard nonetheless echoed the committee’s tighter, sooner, faster line on CNBC on Friday, explicitly calling the Fed’s moves on Wednesday “hawkish.” The frank talk scared markets, forcing the Dow down 1.6%, its biggest one day drop in a month.

Bullard underscored that the Fed would be exploring a slowdown of its $120 billion monthly asset purchases, cautioning that it would take “several meetings” to get plans organized. Powell confirmed in his press conference on Wednesday that the FOMC had discussed tapering the market subsidies, officially moving from the “talking about talking about” phase into actually talking.

These purchases raised bond prices and lowered their interest yields. This made debt easier to take on, stimulating the economy in the short-term, while boosting stock prices. Bullard’s forthright comments let investors know to expect a regime change soon.

But maybe not soon enough. Until those “several meetings” pass, the Fed will keep pouring cash into the market and hoarding Treasury bonds while money markets suffer from an excess of cash and shortage of Treasury bond collateral. Raising the IOER and reverse repo rates was supposed to relieve this problem, but Thursday saw an unbelievable 68 counterparties put $765 billion into the facility. This represented a one-day increase of $235 billion from Wednesday.

For context, just six weeks ago we were fretting about $143 billion in daily reverse repo uptake. The surge suggests that the 0.05% bumps weren’t enough to change market dynamics, which means that more increases could be on the way. The Fed funds rate tracks closely with these administered rates: past loose policy is now forcing tighter policy sooner.

This has big long-term implications. Remember that this economic system suffers from endemic downward pressure on profit rates as businesses over time shift investment away from labor (which creates new value) into fixed capital (which does not). The pandemic only added to this pressure, as new research from the San Francisco Fed discovered that pandemics going back to the 14th century result in decades of blunted returns with labor killed off and capital left intact.

Now markets see these long-term trends and the Fed’s new hawkishness combining to force assets into a “U-turn on easy street.” After Wednesday, the Treasury bond yield curve flattened sharply: short-term rates popped and long-term rates stayed put. The move implies a low r* -- “r-star,” the economy’s “natural” interest rate. Rates higher than the r* drain away growth as debt service costs exceed income increases.

Major investors see near-future rate hikes exceeding the r*, in turn weakening the economy, resulting in lower growth and inflation at the far end of the curve.

The Fed funds rate is now at effectively zero, and adjusted for inflation is actually in negative territory. Markets believe the economy can’t grow faster than this, meaning that without state intervention the economy is stuck in perpetual decline. But now we’re seeing hard limits to those interventions, raising the question: where can we go from here?

Nobody knows, but Wall Street suggested last week that it isn’t anywhere good.

China keeps reducing risk, moral hazard

China’s Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) published new rules on Friday reigning in so-called “cash management products” (CMPs), a $1.15 trillion market of risky investments and an important source of funding for property developers in the country.

CMPs are investment plans issued by banks that offer higher yields, and allegedly lower risks, than money market funds sold by asset managers. Money market funds have to date been more tightly regulated than CMPs, but Friday’s rules narrowed the gap. Among the new regulations, Chinese banks can no longer use CMPs to buy long-term debt or bonds rated below AA+, the second highest measure of creditworthiness. That will soon force investors to move at least $390.5 billion out of CMPs to stay compliant.

This move was all part of the Communist Party of China’s ongoing crusade against risks -- not only at home from a loosely-regulated financial sector, but to insulate the Chinese economy from potential turmoil abroad. Taken together, the move reflects a different set of priorities for the world’s most populous country compared to its rivals.

A few days before the new rules, CBIRC chairman Guo Shuqing, who is also the party’s committee chief at the People’s Bank of China, warned that monetary policies in developed countries -- like the cash glut drowning short-term interest rates in the U.S. -- have become “unprecedentedly loose.” But in China, “the credit risks at banking institutions have intensified” and the dangers of bubbles in real estate are “serious.”

"These measures have stabilized the market in the short-term but require all countries in the world to share responsibility for the negative effects," Guo added.

Beijing began its crackdown on financial risk in December 2019 but the CMPs largely avoided the party’s scrutiny, growing by 74% as investors looked for the rich returns offered by the opaque financial instruments. Property developers such as China Evergrande Group -- the country’s second largest developer -- looked to the products as a source of liquidity to cover their debts, and to keep up in bidding wars over development sites.

Without the CMPs, developers will have trouble raising funds to repay their debts: exactly the reduction -- and transfer -- of risk the Communist Party wants to achieve. At the same time, Beijing is putting pressure on local governments to reign in developer bidding frenzies by changing the way land parcels are put up for development. For years, cities opened up land for developers with no pre-determined schedule, with developers jumping in to aggressively bid up the prices. The companies would sell homes on the land before construction completed to cover their debts.

The predictable result: rising housing prices and highly-indebted developers. This in turn led investors to buy property “not for living, but for investment or speculation, which is very dangerous,” Guo said back in March.

The new regulations already appear to be working. Shares of Evergrande Group and other property developers fell on the news of CMP regulations, with analysts expecting a hit to bank revenues.

The new regulations cap the maximum leverage level of CMPs at 120% and limit investment areas to short-term bank deposits and central banks bills, while forbidding these products from investing in stocks and convertible bonds. Beijing has also limited the duration of the investments at 397 days -- longer than the 120-day average of money market funds, but shorter than the unlimited duration before.

Overall, analysts expect a “soft landing” this year for China’s housing market, stabilizing prices, bringing down prices of raw materials, with some heavily indebted developers likely to default.

CBIRC is limiting the fallout from this risk by requiring banks and insurers to create “living wills” -- contingency plans -- in case they run into trouble. That will include requiring banks to first use their own assets to cover losses, and to ask shareholders for help before turning to the government for support. “They should prevent aggressive behavior to shoulder too much risks, and prevent the moral hazard of over-relying on public rescues and support,” the regulator stated earlier this month.

By contrast, extraordinary stimulus into U.S. markets by the Fed has caused excess cash to flood into an array of “risk assets” where investors hope for any kind of return. Different priorities -- creating the conditions for the exact kind of global economic turmoil China’s regulators are worried about.

Rapid Round

Iran elects Raisi, hopes for deal restored

Ebrahim Raisi, a prominent jurist backed by the conservative Combatant Clergy Association, won Iran’s presidential election held on Friday. His top priority: restoring growth to an economy battered by U.S. sanctions, a pandemic, and low oil prices now on a gradual, upward climb.

Raisi campaigned on boosting industrial production and reining in inflation -- it’s currently hovering at more than 50% -- and to build four million housing units for the country’s poor. This could possibly include a revival of the Mehr housing cooperatives, which aimed to construct cheap residences available with 99-year lease contracts, but which slowed down in recent years.

Analysts also expect that Raisi -- a possible future successor to Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei -- will want to return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action nuclear deal, which the U.S. unilaterally withdrew from in 2018, given the positive economic impact from ending sanctions.

Iran’s state energy companies have also been investing in production and export capacity in preparation for exactly that. “Both reformist and conservative factions in Iran are fully aware that a new nuclear agreement ... is highly popular,” Brandeis University economist Nader Habibi wrote.

Toshiba faces reckoning for corporatist moves

Shareholders at Japanese industrial giant Toshiba are calling for the resignation of Chairman Osamu Nagayama and other board members after an independent investigation revealed the company’s leadership colluded with the Japanese government to “beat up” foreign investors.

The crisis at Toshiba has escalated for weeks, bringing down the conglomerate’s CEO in April, and is now heading to a clash at the annual shareholders’ meeting this week. Japan has attempted to boost low- and slow growth for years by freeing up capital markets and wooing foreign investors to buy shares in indebted corporations such as Toshiba.

But those investors ran into the realities of Japan’s quasi-corporatist economic model. The investigation into Toshiba’s practices showed that MITI, the trade ministry, would pressure investors while the company would offer a compromise on director appointments. Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, who was then a senior aide to former P.M. Shinzo Abe, was part of the deals behind the scenes.

MITI’s high-pressure tactics targeted Harvard University’s endowment fund, Singapore-based Effissimo Capital Management, and 3D Investment Partners. A letter from 3D last week called Tokyo and Toshiba’s strategy “deeply troubling.”

Disclaimer

Our only investment advice: Money still talks.

Contact us with questions, feedback, or stories we might have missed.