Why is liberalism collapsing?

Basic business forces put the system on a doomed trajectory

Welcome to a special edition of Contention! This week we wanted to dig deeper into some of the forces behind the business headlines, so this column is a little longer than normal: it should take just under 10 minutes to read.

If you haven’t subscribed yet, please do so here:

Last week U.S. President Donald Trump threatened to foment unrest in order to block Congress from certifying his successor’s victory in November’s elections. Trump’s former National Security Advisor, Michael Flynn, took things even further, calling for martial law to keep Trump in office. With a substantial portion of the electorate rejecting the legitimacy of Biden’s victory, such a move could have significant popular support.

Markets do not seem worried -- the Dow was up 0.4% last week, the S&P 500 1.3% and the Nasdaq 3.1%. Still, such unprecedented authoritarian threats demand examination. How did it come to this, the flat rejection of basic liberal norms?

The answer is one of the “Big Three” forces Contention believes are guiding the trajectory of the world economy today: a declining rate of profit sapping liberal governance of its necessary social foundations. This phenomenon is an unavoidable aspect of our way of life, and understanding it is key to making sense of -- and changing -- the world around us.

Its roots are in the basic foundations of money making. Businesses combine raw materials, machinery, facilities, and labor into value-added products they can sell for a profit. The materials, machines, and buildings can’t add value to themselves -- only labor can make them more valuable.

Businesses that can produce more output more efficiently will generally make more money, so owners over time tend to invest their profits into more and more sophisticated plants and machinery. That is to say, they put more money into the parts of their business that do NOT add value.

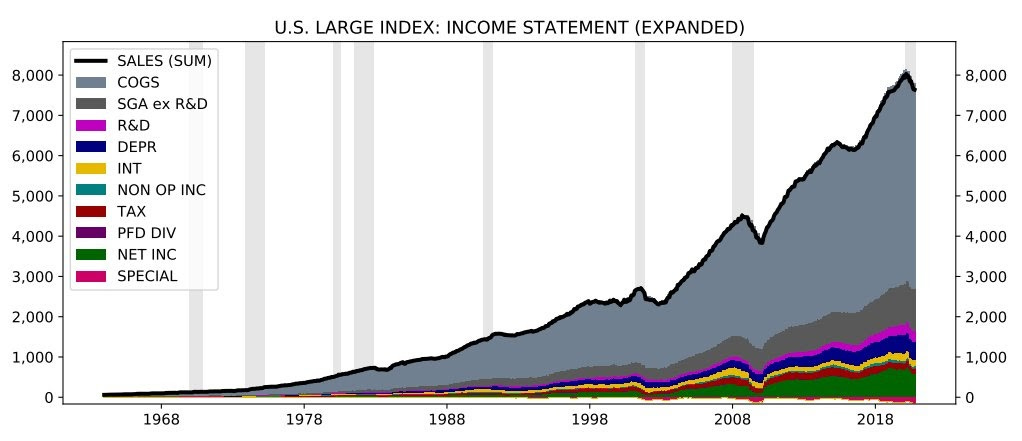

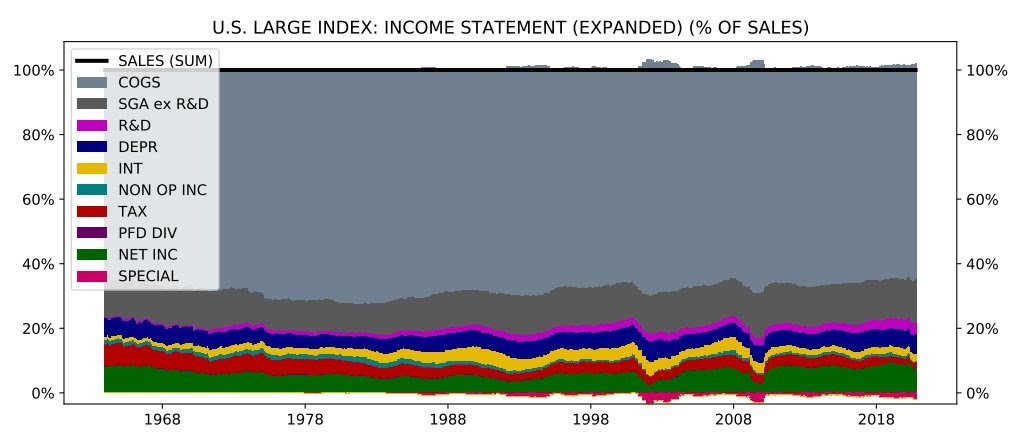

The result: an overall tendency of the rate of profit to fall. Just last week economist Jesse Livermore showed off a new tool for organizing huge amounts of market data. This chart shows the aggregate income statements of all S&P 500 components since the 1960s:

The chart illustrates an inexorable rise in “COGS” -- the cost of goods and services, the money businesses spend on the labor and materials needed to deliver their primary products. These rising costs mean squeezed margins -- a falling rate of profit over time.

But Livermore shared a second chart that seems to push back on our argument: when shown as a proportion of sales, margins are remarkably steady over time.

This suggests that sales are increasing in the same general direction as business costs. Where is that money coming from? Wages have not grown at anything like this rate.

The answer, of course, is debt. Household debt has consistently grown over these same decades.

The trough between the last economic crisis and this one reflects tightened access to mortgages. If you look at non-housing consumer debt, the growth has continued:

Debt represents future earnings pulled into the present. The upshot of ever increasing borrowing: over time it takes more and more income to pay off the earnings already claimed. Investment advisor Lance Roberts has calculated that it now takes about $4 in debt to generate a dollar in GDP growth. At the beginning of Livermore’s chart it was less than $0.50.

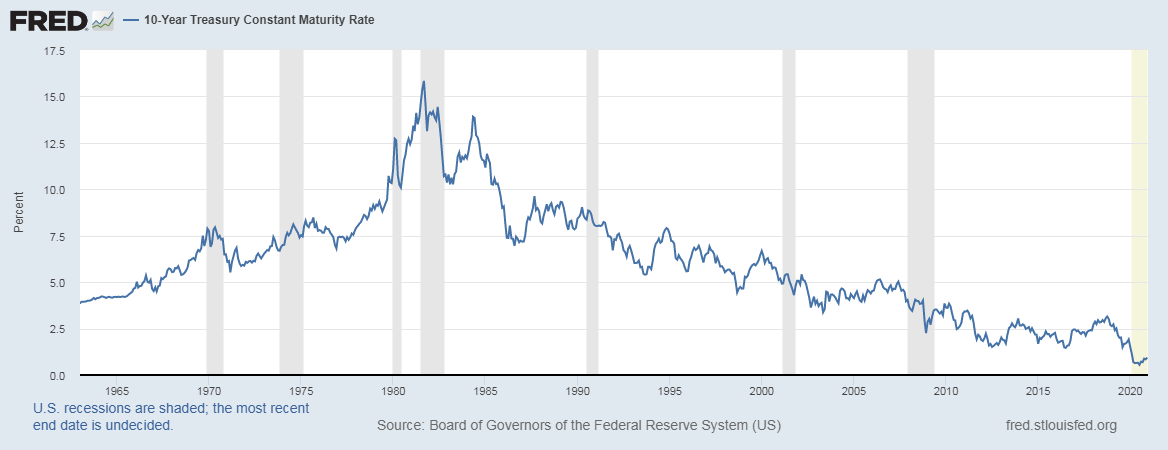

This phenomenon then produces a powerful feedback loop: high levels of leverage suppress growth expectations, which in turn means lower interest rates -- rates reflect anticipated future price increases. This makes debt cheap, encouraging more borrowing and thus higher leverage, starting the cycle over again. The benchmark 10-Year Treasury Bond’s interest rate has been declining for years:

The economy has gotten accustomed to these low rates. But as we noted in our column on 2021 crisis risks, any upward pressure on interest rates either from increased growth expectations or reduced risk appetite -- i.e. from either very good or very bad news -- will ripple through the economy with major consequences.

In recent history, the Fed has responded to this risk by buying up trillions of dollars of bonds, driving up their prices, and suppressing their interest rates (rates move inversely to prices). Some investors even anticipate a possible “yield curve control” policy for the Fed, i.e. a commitment to buy all the bonds necessary to keep long-term interest rates below a certain cap.

This is called “monetizing debt” and it has historically meant kicking the slats out from under your currency. Just last week the Dollar Index hit its lowest point in two years, with a clear downward decline throughout 2020. This degrades consumer purchasing power over time, a fact hidden by official consumer price data rigged to keep cost of living adjustments low:

Remember that inflation-adjusted “real” wages have been largely stagnant over the last 20+ years. But these inflation adjustments use the lower, red line to calculate costs, so workers have actually steadily lost ground in this debt-financed, profit-declining economy.

On the other hand, the dollar’s decline and low interest rates boost stick prices, as demonstrated by 300%+ S&P 500 growth over the last decade.

Rising stocks and falling wages mean a steady shift in resources from labor to capital. This chart shows the proportion of U.S. GDP paid out to workers:

Working people are getting smaller and smaller pieces of an ever shrinking pie, even while their investments -- which tend to be concentrated in pension funds -- are getting hammered by the same low interest rates boosting the bottom line for the rich.

Even worse, these diminishing returns have eroded labor force participation over time:

So now the story is clear: internal business dynamics mean steadily shrinking surpluses which trickle down to working families through shrinking real wages, degraded long-term investments, an eroding position in the economy overall, and rising delinquency. In a word: despair, with U.S. life expectancy in a long-term decline due to “deaths of despair” such as drug overdoses, alcoholism, and suicide.

Liberal theory rests on the idea of a “social contract” where the masses grant power to a governing class that promises to protect the interests of the society as a whole. Whether this reflects historical reality or not, even by its own logic liberalism can’t survive when the ruling class openly advances its own position at the expense of deteriorating conditions for the population at large.

Voters will choose “nothing to lose” illiberal options or simply revolt -- precisely the cycle of unrest, reaction, and deadlock seizing up U.S. politics today. In that context, Trump’s “wild protests” and Flynn’s martial law sound perfectly reasonable. But this force is not caused by one party’s policy: it is baked into the very nature of our economy and even “progressive” forces explicitly refuse to fix it.

We can’t predict exactly how this will express itself over time, but we can anticipate that things will continue to get worse until some sort of epochal economic reset. Contention is committed to documenting the consequences of this phenomenon and the others shaping our destiny today -- stay tuned.

Disclaimer

Our only investment advice: Check out the new Shaun.

Contact us with feedback, questions, or stories we might have missed.