Bad jobs report has a Wall Street silver lining

Plus Guinea’s coup, Saudi’s sale, and trucking’s crisis

Welcome to a holiday week edition of Contention! This one will only take five minutes to read. In it we cover:

Bad jobs report has a Wall Street silver lining

Rapid Round: Guinea has a coup, the Saudis slash prices, truckers keep quitting

Like what you see? Follow us on Twitter and share with a friend!

Bad jobs report has a Wall Street silver lining

The major U.S. stock indexes showed a familiar pattern last week, with the industrial-heavy Dow losing 0.2%, the tech-heavy Nasdaq gaining 1.6%, and the broad-based S&P 500 landing in the middle, up 0.6%. The divergence happens whenever investors expect lower interest rates, a boon for growth stocks but an indicator of weaker growth near-term.

It’s also a tell-tale sign of our times: what’s bad news for almost everybody means big bucks for Wall Street. The only question is how long the party can last with so many people locked out.

The cause of this latest split: the August jobs report, released on Friday. Economists expected 720,000 new jobs for the month, but they only got 235,000. This was down from 1.05 million in July, with hospitality and leisure leading the trend, turning from an average growth of 350,000 jobs per month to a flatline.

The COVID-19 delta variant surge was the obvious culprit for the downturn, but the pandemic has a brightside for capital: a weaker job market means an almost certain delay in Fed plans to taper asset purchases this year. Continued bond market subsidies will pin down interest rates, inflating stock prices as money flows out of safer assets in the hunt for yield.

Notably, the slowdown was not demand-driven, with employers continuing to report a record need for labor and layoffs hitting a 24-year low in August. Instead, it appears to be supply-driven, with workers hesitant to go back to heightened risk of illness -- and for the unvaccinated, death. This week the hypothesis that blames enhanced unemployment payments for the shortages will finally be tested, as the benefits come to an end across the board.

In total, 8.9 million people lost all of their income yesterday -- long-term jobless workers (out of work for more than 26 weeks) and self-employed and gig workers. An additional 2.1 million will lose the extra $300 a week all recipients received over the past year. Altogether, families will lose $5 billion a week in income, possibly the biggest loss of government benefits in U.S. history -- welfare “reform” in the 1990s only cut off six million families over the course of four years.

So far, there is no evidence that this austerity will assuage labor market problems whatsoever. JPMorgan analysts reported last month that they found “zero correlation” between job growth and benefit policies in the states that have already ended some of them. Instead, the loss of consumer demand in those states may have contributed to the service industry woes seen in Friday’s job report.

Relying on blunt tools like benefit cutoffs and money printing to fix an unprecedented labor market crisis is the policy equivalent of whacking the side of the T.V. to make it work. But policymakers have few other options as long as they refuse to admit the problem’s most likely causes.

First and foremost: their deafening silence around the most obvious reason for reduced labor supply in the context of a deadly plague -- the plague itself. The Economist clocks U.S. excess deaths since the pandemic began at 745,780 as of early August, 23% higher than the official estimate of 608,070. Add on top of that cases of chronic illness, with 10-30% of the country’s 40 million COVID patients suffering from “Long COVID,” and you get millions of workers missing from the labor force due to death and debilitation. Few stories in the mainstream business press have even mentioned this possibility.

Second, the Fed’s interest rate manipulation has inflated not only stocks, but also the most important capital asset in the economy by far: housing. Last week, the Case-Shiller Index for June (the report lags two months) surged 18.6% from the year before, a new record. This marked the third straight month of record gains in home values.

For landlords, these rising values mean declining rental yields -- the ratio of their rental income to the value of their properties. This leaves them with three choices:

accept a lower yield

raise rents

sell the property and make their profits from the asset sale instead of the income flow.

Very few are choosing door number one, and private equity firms glutted on this same asset pump are eager buyers right now. The higher price they pay means higher financing costs and higher rents for tenants. The inevitable displacement as inflation-eroded wages fall behind housing costs means that the very communities with the hottest economies and the highest demands for services are also the places where workers are being priced out the fastest.

The result: service industry job growth at a 14-month low in August, again in spite of record employer demand. This then cascades into plummeting consumer expectations, with confidence dropping more than 10 points last month, a major downside surprise from already pessimistic expectations.

This dread makes perfect sense: either the slowdown sets in, encouraging more central bank market activism, displacing more working people and eroding returns on labor; or the government turns to austerity, encouraging the slowdown and replacing the labor shortage with a job shortage. And all along the way, more people get sick and die, a mere distraction for business.

For now, investors have a lot to be optimistic about, as the same trends that have made the pandemic a source of wealth and hope for them seem set to continue indefinitely. But eventually they’ll learn that all things come to an end, something 745,780 families already know all too well.

Rapid Round

Aluminum prices surge after Guinea coup

Military officers led by a special forces leader overthrew and arrested Guinea’s President Alpha Condé on Sunday. Col. Mamady Doumbouya, a 41-year-old former member of the French Foreign Legion, has declared a nationwide curfew following the coup. Condé was Guinea’s first democratically-elected president, serving since 2010.

Doumbouya has exempted mining companies from the curfew. Guinea is the world’s top exporter of bauxite, used to manufacture aluminum, and world aluminum prices rose to a 10-year-high upon news of the coup.

Aluminum prices had already risen 50% over the past year given logjams in shipping, adding further pressure on the global economy. China also cut back production to meet its climate goals and vowed to crack down on speculation to stabilize rising prices.

In Guinea, the expansion of bauxite mining under Condé brought jobs, but also pollution and mining companies forcing farmers from their lands, provoking protests in recent years. “The population sees the financial investment a company is making,” one Guinean mining official told a U.S. NGO. “They see taxes being collected, trucks taking bauxite from their farmland abroad, they breathe the dust, and they ask, ‘what do we get out of it?’”

Saudi cuts oil prices on falling demand

Saudi Arabia slashed oil prices for sales to Asia by more than analysts expected on Sunday. This marks Riyadh’s first price reduction in five months, and comes as the weak U.S. jobs report on Friday suggests slower fuel demand in the months ahead.

Fuel consumption in the U.S. has been on an upward swing, but Asian customers requested less crude from the Saudis due to their own impact from delta. Oil-trade analysts say Riyadh sees a weak demand situation that requires a lower price to stay competitive. At the same time, a significant portion of U.S. production remains offline in the Gulf of Mexico after Hurricane Ida.

The Houthis in Yemen also fired a ballistic missile on Sunday, which forced Saudi Arabia to lock down several Aramco facilities, but there was no apparent damage. A Houthi attack on an oil field and processing plant two years ago halved Saudi Arabia’s oil production for weeks.

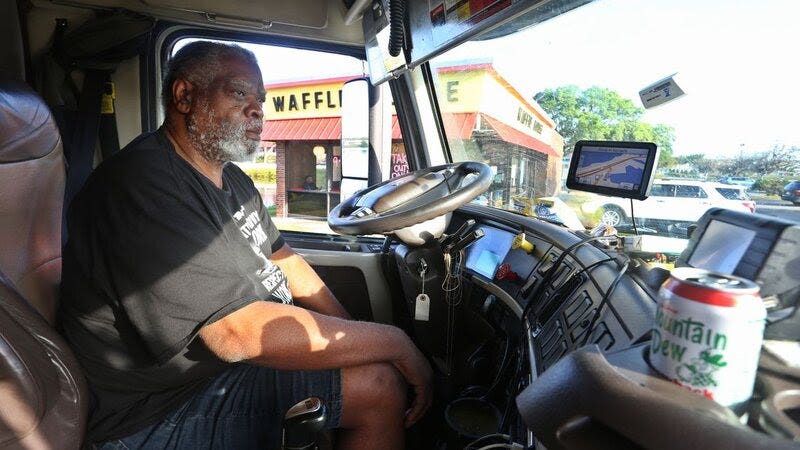

Burnt-out truckers have had enough

New data released last week reveals the extent of the labor shortage crisis on the U.S. trucking industry. In January 2020, there were around 465,000 truckers moving freight, but that’s now down to 430,000, according to the American Trucking Associations. “The driver shortage in the U.S. is getting even worse,” ATA economist Bob Costello said. “It is as bad as it has ever been.”

One reason: burnout from exhausting work away from home and low pay. As drivers drop out, employers put pressure on the remainder to make up the delivery gap in a vicious cycle. This is also true in Europe. “It’s like a prison, it’s not a job,” one trucker for Lithuania’s Baltic Transline told the Financial Times. “You do it like a zombie.”

An aging workforce is contributing to the shortage, with around 57% of American truckers older than 45, and 23% over the age of 55. The industry has likewise struggled to recruit women drivers, who often cite safety as their top priority in surveys within the industry. Walmart is offering an $8,000 signing bonus for some drivers, but increasing pay throughout the industry could raise the costs of goods, including food, at a time when world food prices are at a decade high -- up 32.9% year-over-year.

Disclaimer

Our only investment advice: Hang it up and see what tomorrow brings.

Contact us with thoughts, questions, or stories we might have missed.